Elie Saab Maison opens in Harrods London

Harrods began as a wholesale grocer and tea merchant in east London, first opening its doors in 1834. Since then, the shop has grown to become a world famous department store, known for its exclusive, luxury merchandise and “anything is possible” service.

Now, in a journey that started in Milan last September, much loved brand, Elie Saab, founded when the leader in Haute Couture was just 18 years old, comes to Harrods with Elie Saab Maison. The collection, designed as a holistic partnership between fashion and interiors, offers statement pieces made with Saab’s signature styling.

Displayed in the Interiors Department on the third floor, the brand will occupy 120 m2 comprised of a large living and dining area, and a bedroom conceived as a luxurious suite. The suite will display the Voyage Royale bed, Essence bedside tables and the Valet de Nuit, an integrated series of mirrors and storage compartments.

The space also houses a generous selection of lovely accessories that promise to add a touch of personality to any room in the house, including decorative cushions and plaids along with lighting and rugs. The boutique will be re-designed each season to reflect regular additions to the Maison line.

Harrods customers will also be treated to an exclusive preview of the first pieces of the brand’s Home Office Collection that Elie Saab plans to unveil sometime next year in Europe.

The art of building the impossible

Mark Ellison is a carpenter—the best carpenter in New York, by some ac- counts, though that hardly covers it. Depending on the job, Ellison is also a welder, a sculptor, a contractor, a cabinetmaker, an inventor, and an industrial designer. He’s a carpenter the way Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect of the great dome of the Florence Cathedral, was an engineer. He’s a man who gets hired to build impossible things.

Ellison is 58 and has been a carpenter for almost 40 years. He is a big man with heavy, sloped shoulders. He has thick wrists and meaty paws, a bald head and fleshy lips that protrude over a ragged beard. There is a bone-deep competence about him that reads as solidity: he seems built of denser stuff than others. With his gruff voice and wide-set, watchful eyes, he can seem like a character out of Tolkien or Wagner: the clever Nibelung, fabricator of treasures. He loves machines and fire and precious metals. He loves wood and brass and stone. He bought a cement mixer and was obsessed with it for two years. What draws him to a project, he says, is the potential for magic, the unexpected.

“Nobody ever hires me to do a conventional building,” he said. “Billion- aires don’t want the same old thing. They want something that no one has done before, and that might even be ill-advised.” Ellison has worked for David Bowie, Woody Allen, Robin Williams, and dozens of others he’s not allowed to name.

What did Europe smell like in the past?

Get a whiff of this new sensory experience. Odeuropa , a $3.3 million, three-year multinational project will collect and recreate smells of the 16th–early 20th century in Europe and marry them with historical, literary analysis, chemistry and machine learning. Smell has been getting a lot of attention in different communities so the project is pioneering and timely as it was launched in the first year of COVID-19 anosmia where sensory deprived lockdowns were in place.

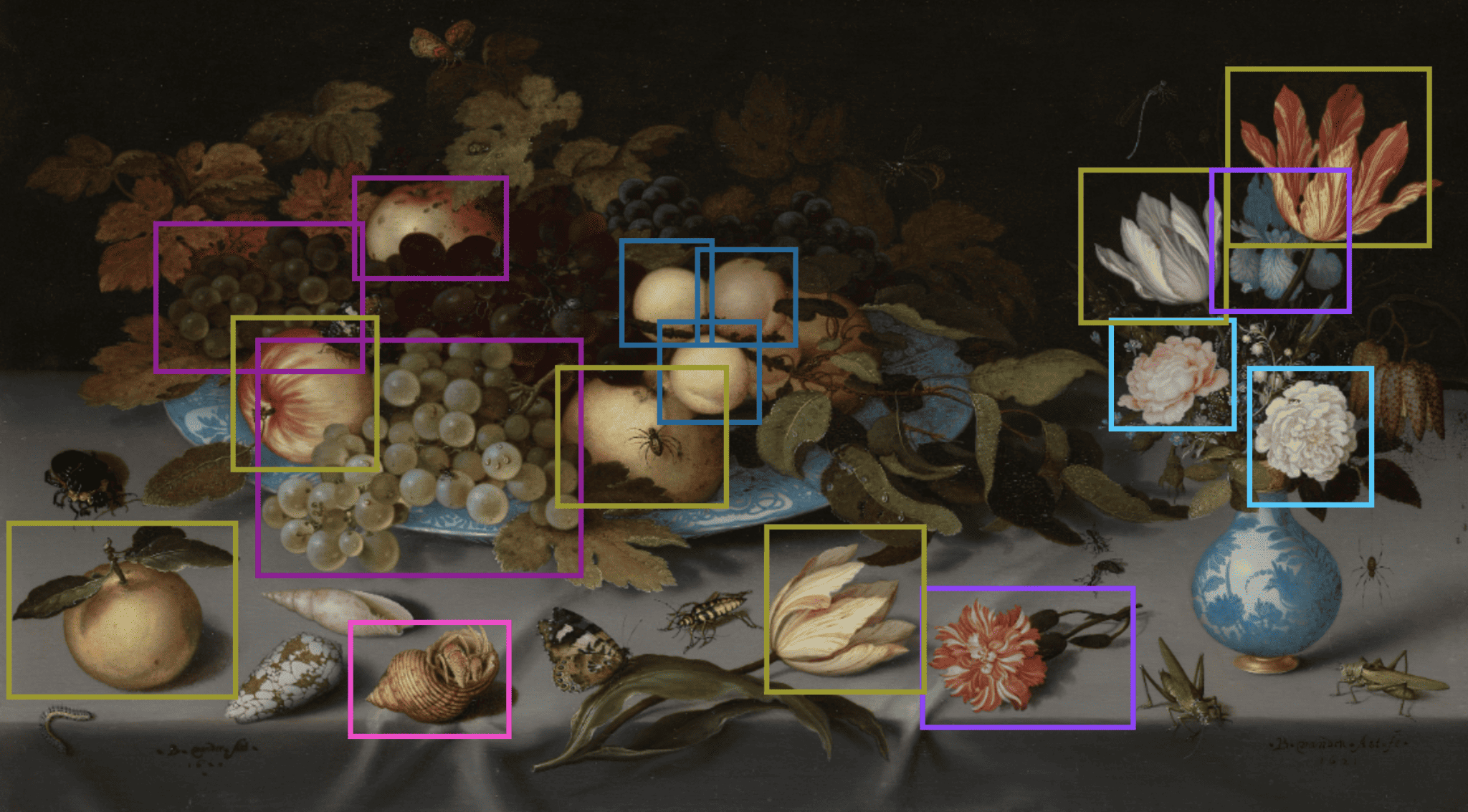

Odeuropa opens up a new sensory experience of history. Researchers will create a catalogue of past scents by digging through 250,000 images and thousands of texts (in seven languages), ranging from medical descriptions of smells in textbooks to labels of fragrances in novels or magazines. Machine learning will help to cross- analyze the plethora of descriptions, contexts, and occurrence of odour names (such as tobacco, lavender, and probably horse manure). This catalogue serves as the conceptual basis for perfumers and chemists to create fragrant molecules fitting 120 of these descriptors.

Odeuropa identifies an omission that it aims to rectify: the increasing absence of material presence that smells seem to convey. Smells may seem intangible and immaterial to many people but the unique relation between odours and memories, allows us to engage with our history in a more emotional way.